BY DONALD H. KAGIN, PH.D.

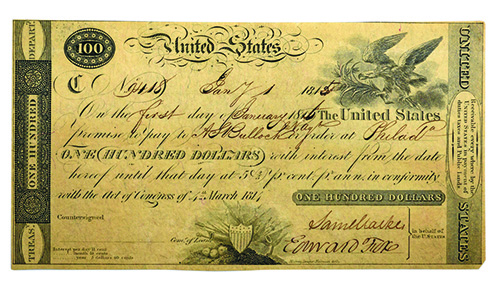

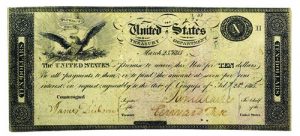

It is now clear that the first circulating currency issued by the United States was not the Demand Notes of 1861 as was commonly believed for decades, but the Treasury Notes of the War of 1812 printed in 1815 forty-six years earlier.

The War of 1812 triggered our nation’s first severe financial crisis since the Revolution. Yet for the most part, it is a forgotten conflict. Often called our nation’s, “Second War of Independence,” the conflict erupted after an extended disagreement with Great Britain over trade tariffs and their continued capturing and impressing of U.S. citizens for British maritime service, including prosecuting their war against France. The war lasted more than two years, and ended in something of a stalemate but did confirm American Independence.

War of 1812 Prompts Return Of Currency

Following the disastrous attempts at issuing paper currency during the Revolutionary War, which inevitably led to massive inflation and currency devaluation, Congress was very reluctant to again authorize the printing of paper money. But as the conflict dragged on it became increasingly apparent that to provide the nation with necessary funds and an adequate medium of exchange to conduct the war, that emitting banknotes was inevitable. The final issue of “small” Treasury Notes under $100 denominations, served as circulating national currency, albeit without the obligation of acceptance that comes with legal-tender status.

These Treasury Notes significantly helped to provide a medium of exchange for our fledgling nation during the most difficult part of the war and as such are among the most important currency ever provided by the United States.

A total of five issues between 1812 and 1815 totaling $36 million in denominations of $3 to $1,000 were emitted. The notes proved to be extremely successful and were fully subscribed and accepted by banks and merchants.

Pre-1812 Finance

From the adoption of the Constitution until the War of 1812, the U.S. government had financed its deficits by borrowing. Until 1792, major loans were procured primarily from Holland or through funding operations, while temporary or small “bridge” loans were obtained from consortiums of prominent capitalists or from the four existing private banks, among them the Bank of North America and the Bank of New York.

Almost all revenues, for whatever purpose, came largely from customs. Between 1801 and 1806, this amounted to between $11 and $13 million annually, with a small supplemental income from the sale of lands, scanty funds with which to fight a world power like Britain.

Until the financial emergencies occasioned by the War of 1812, the government was firmly committed to a hard-money policy. The Constitution gave Congress the power to “coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures.” The question of paper money was vigorously debated in 1787 by members of the Constitutional Convention. Both a proposal for the inclusion of a provision authorizing its issue by the national government and one prohibiting issue was defeated.

The political thinking of the time, succinctly expressed by Virginia’s U.S. Representative James Madison, was that the use of paper money might lead to mass abuse and proliferation, reminiscent of the vastly depreciated Continental Currency. (The original impetus for the issuance and use of the latter was to circumvent British laws forbidding the minting of coins by the colonies.)

On the other hand, the outright prohibition of paper currency would tie the government’s hands in cases of temporary emergency. The Constitution, therefore, resolved the dilemma by specifying nothing. It did, however, proscribe the issuance of “bills of credit” by the states and, by implication, the federal government.

The Bank of the United States

As Secretary of the Treasury under President George Washington, Alexander Hamilton proposed to Congress in 1790 a “financial institution to develop the national resources, strengthen the national credit, aid the Treasury Department in its administration and provide a secure and sound circulating medium for the people.” This national bank would supersede local and state banks and was necessary, Hamilton argued, to collect taxes and administer public finance, and provide a source of loans to the Treasury.

Opponents, led by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and his Democratic allies, warned of potential abuse, stating that the bank was not provided for in the Constitution, would destroy free institutions and would benefit only a few.

Nevertheless, the Hamiltonian Federalists’ view prevailed, and on February 25, 1791, the First Bank of the United States was established and granted a 20-year charter. Shares of stock were sold to fund the bank, with almost 75 percent going to British interests.

Once established, this institution became the primary lender of short-term funds to the government (although a few small loans at high rates were sold directly to the public during this period).

The bank offered many advantages, including the safe-keeping of public monies; the instantaneous transmission of public monies anywhere in the nation; an increase in circulation to facilitate the collection of revenues; the providing of loans to the U.S. government; and the ability to issue notes payable in gold or silver at the bank. Although not accorded legal-tender status, these notes were even receivable for all payments to the U.S. government.

Gallatin’s Policy

During the Republican administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, the architect of the government’s fiscal system was Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin. His major objective was the reduction of the national debt to the exclusion of all other considerations. Prior to 1808, Gallatin declined to augment Treasury receipts except by temporary loans, even though a year later he belatedly conceded the possible need for internal taxes.

It was not until early 1812 that Gallatin’s optimism waned, and he intimated that the extraordinary, impending expenses of military and naval services would require funds in excess of current revenue.

With duty revenue down from $13.3 million in 1811 to $9 million in 1812 (mainly a result of the Embargo Act of 1807, which prevented trade with the warring nations of France and Great Britain and ensured U.S. neutrality), and a corresponding increase in expenditures to $22 million, Gallatin suggested a 100-percent tariff increase. He justified the proposal on the grounds that “this mode [increased duties] appears preferable…to any internal tax.”

The result of this fiscal policy was the absence of any system by which internal revenues could be collected. Gallatin conceded his error in 1831 when he admitted that he should have recommended such taxes in 1812. Acting upon the Treasury Secretary’s recommendation, Congress doubled tariff duties.

The First Bank’s End

Meanwhile, opponents of the First Bank of the United States had gathered more Congressional allies. One of their main concerns was the high-interest rates being paid to foreign stockholders (mainly British). When the bank’s charter came up for renewal in 1811, opponents had the necessary votes to defeat it.

Additionally, since the foreign shareholders of the bank were paid off in specie, little precious-metal coinage remained in America. Unfortunately, the bank’s demise could not have come at a worse time, as the renewed hostilities with Great Britain had reached a climax.

Britain was already involved in a war with France, and its seamen routinely boarded U.S. merchant ships, ostensibly looking for deserters or military supplies. They then would impress American sailors into service in the British navy.

Negotiations with Britain to halt this abuse and its blockades of American ports were futile, and on June 18, 1812, President James Madison signed Congress’ declaration of war against Great Britain.

The First Treasury Notes

Unable to sell long-term debt advantageously and without the Bank of the United States to provide temporary financing, Gallatin recommended the use of Treasury notes. This was not altogether a new suggestion since he had mentioned that particular mode of public financing as early as February 1810.

The bill’s Congressional opponents voiced every possible argument against the use of paper money. They claimed the notes were not equal in value to gold or silver and therefore would not be accepted by banks or people prejudiced against the government paper.

They stated that, if received, the notes would circulate at a discount, further subverting public and private credit, and would, like the Continental Currency, greatly depreciate. The very need to use paper money was, the opponents felt, a confession of impending bankruptcy. If such notes had to be issued, a direct tax should be imposed upon their redemption.

Proponents of the bill, however, were more pragmatic. To begin with, they argued, there was a shortage of circulating medium. Silver was already in limited supply because shiny new coins were in demand in Latin America and abroad for the China trade, while gold was undervalued at the Mint and hoarded, leaving little to be delivered for coinage.

The alleged poor and depreciated quality of many bank notes (especially since the retirement of the Bank of the United States’ circulating notes) ensured that a soundly managed Treasury Note currency would be a welcome addition to the U.S. economic system. Depreciation would be checked by their acceptance for taxes and public use, while their value would be sustained by the fact that the banks would hoard them as interest-bearing reserves.

Representative William W. Bibb of Georgia, a Treasury bill proponent, responded to the objection that the proposed notes were similar to the heavily depreciated Continental Currency. He pointed out that the latter bore no interest and, what became perhaps the most important reason for the Treasury Notes’ success, that there was a pledge to redeem the bank notes by a certain date.

The positive arguments prevailed, aided by the inability of the opposition to fill the Treasury by any other means, and the bill authorizing $5 million in Treasury Notes passed the House of Representatives on June 17, 1812, by a vote of 85 to 41. Final enactment of the bill came on June 30, 1812, nearly 12 days after war was declared.

Terms & Success

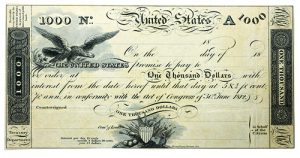

$15,000,000 in denominations of $100 and $1,000 notes were authorized and by December 1812 and were fully subscribed by the banks. They bore interest at 5.4% or 1 ½ cents a day per $100.

Virtually all of these first issues were redeemed by 1814. Subsequent issues followed a pattern in which Congress first attempted to raise funds by floating long-term loans and then making up the difference with the issue of Treasury Notes.

Congress, therefore, authorized a second issue of $5,000,000 in Treasury Notes on February 25, 1813.

The third issue of March 4, 1814 authorized another $10,000,000 of Treasury Notes. Unlike the first two issues that only authorized $100 and $1,000 notes, this issue and the next included $20 notes.

The fourth Treasury Note issued on December 2, 1814 approved an additional $10,500,000 of Treasury Notes, but for the first time not all were fully subscribed ($8,318,400). Only $100 and $20 notes are believed to have been printed. Most of these first four issues were redeemed.

Issuance of Small Denomination Treasury Notes

With new loans and fiscal revenues far from adequate to prosecute the war, a new monetary expedient was necessary. Specifically, the Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee argued for a circulating currency of “small” (under $100) denominations payable to bearer, transferable by delivery and receivable in all payments for public lands and taxes. On February 24, 1815, Congress authorized $25,000,000 of these small Treasury Notes.

A few days later, the war ended and only $4,969,400 of $100 notes bearing interest at 5.4% and $3,392,994 of the small $50, $20, $10, $5, and $3 denominations were actually issued (although a total of $9,070,386 worth were reissued).

The latter bore no interest, thereby circulating as money. The small notes were used to purchase goods and services by individuals, pay customs duties by merchants, and acted as cash reserves for banks, thus preventing them from being discounted. As a result, they became the first circulating currency of the United States.

The introduction of these Treasury Notes caused an expansion of the country’s money supply and a corresponding rise in prices by acting as bank reserves.

Similar to our currency today, they were not convertible into silver or gold specie, bore no interest, and were receivable in payment of government dues and taxes. Their utility as all but legal-tender issues—and the government’s promise to redeem them by a certain date—prevented their massive depreciation, as was the case with some earlier colonial issues and later Civil War paper.

In New England, they sold at a premium since they substituted for specie, while in the south and West there was less interest since there were fewer debts to the government. Not only were the Treasury Notes our first circulating notes, but our most successful.

Editor’s Note: This article is from Kagins’ book, “Treasury Notes of the War of 1812.” To purchase the limited edition hardbound book, email info@kagins.com, call (888) 852-4467, or visit www.kagins.com/inventory/books/treasury-notes-of-the-war-of-1812.html.