Editor’s Note: This is part of the ‘Money of British Monarchs’ series of articles.

By R.W. Julian

At one time or another, most of us have seen references to the Victorian Age, named after Queen Victoria, who ruled Great Britain from 1837 to 1901. Modern writings often speak of Victorian homes or clothing styles.

Once, however, it also was popular to discuss the Edwardian era, named after King Edward VII, who succeeded Victoria but ruled until only 1910, when he died at the age of 68.

Influence and Impact of the Edwardian Era

In the early 1900s, when Edward was king, the world of fashion and design fell in love with the Edwardian era, and his short reign was famous for innovations in many fields. But, as with all such popular fancies, the world went on to other matters after Edward’s death in May 1910. The horror of World War I, which began in 1914, would soon erase many of the pleasant memories associated with Edward VII.

Edward’s coinage was rock-solid in value and struck at a time when gold and silver were the main pillars of commerce. His strong portrait conveyed a sense of calm and stability at a time when these were things that mattered in Europe and elsewhere.

His mother, Victoria, had become queen of Great Britain upon the death of William IV in 1837 and ruled for over 63 years, one of the longest reigns in modern times and the second-longest in British history, surpassed only by the nation’s current monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, who has now reigned for over 65 years.

Shortly after Victoria’s reign began, she married Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg, Germany, and their first child, Albert Edward, was born on Nov. 9, 1841. Victoria and Albert also had several other children, some of whom married into European royalty of the highest rank.

Ranking Reign

The young Albert Edward was soon named Prince of Wales, a title by which he was almost universally known until he became king in January 1901.

His early upbringing was normal for royalty, except that he had the added responsibility of learning how to rule so he would be prepared when that time came. He was not an avid student, although he did master several languages and had a good analytical mind for solving problems.

The prince was given to traveling and in the fall of 1860, he came to the United States, the first member of the British royal family to do so since 1776 and the American Revolution. He visited many historic sites along the East Coast, including the tomb of George Washington, and was received with parades and other festivities wherever he went. New York was especially hospitable and staged a massive parade in Edward’s honor in early October.

For diplomatic reasons, the prince officially called himself Baron Renfrew, which actually was one of his more obscure titles—but this, of course, fooled no one and the newspapers and magazines of that day openly referred to him as the Prince of Wales.

Royal Visit Helps Repair International Relations

The United States and Britain had not always been on the best of terms in the 1840s and 1850s, but the royal visit was so overwhelmingly successful that it did much to repair some of the minor differences that had arisen.

In December 1861, not all that long after the prince’s return to London, his father, Prince Albert, died, an event from which Queen Victoria never really recovered.

She went into seclusion but did not trust her eldest son, the heir-apparent, with any state business. Her ministers continued to bring important government papers to her—and her alone—until 1898, when she grudgingly allowed the Prince of Wales limited exposure to the inner working of the British government.

In the meantime, as a result of Prince Albert’s earlier matchmaking, the Prince of Wales was introduced to Danish Princess Alexandra (1844-1925) in September 1861. The attraction between the two blossomed and they were married in March 1863.

Prince of Wales’ Legacy

The marriage was a true love match, but the Prince of Wales also had a roving eye and was notorious for his many mistresses, some of whom were well known in their own right; actresses, for example, often caught his fleeting fancy.

Albert Edward and Alexandra had several children, the eldest being Albert Victor (1864-92), who died tragically at a relatively young age. The next in line was the future George V, who ruled after the death of his father in 1910. There also were three daughters, as well as a son who lived only a few hours after birth.

From the 1870s on, the Prince of Wales traveled widely, especially in Europe. He considered himself a roving ambassador for the government, although Victoria was somewhat less than thrilled to see him carrying out this largely unofficial role.

The prince was instrumental, however, in smoothing over international problems on several occasions and was well regarded by the diplomatic staffs of most European countries.

Difficult Diplomacy With Germany

The one country that perhaps caused him the most trouble was the Germany of Kaiser Wilhelm II. The commercial and political interests of the two countries often clashed, and the prince made it a priority to pursue solutions where possible. More often than not, however, the problems were insoluble.

In between his royal visits and quiet diplomacy, the prince had quite another passion besides his many mistresses. Card playing was extremely popular in Britain, as in virtually every other European country at the time, and he was addicted to numerous card games.

One of the games was baccarat, which required both luck and skill. In one instance, a fellow player was accused of cheating and matters soon got out of hand. The accused player sued those who made disparaging comments about him and the prince was required to testify in court in 1891 about the accusations, a duty which did not endear him to the public or the media.

In the late 1890s, once he had been taken into the inner workings of the government by Queen Victoria, the Prince of Wales expanded his diplomatic efforts to match his newly found authority. His close family connections, for example, with the kaiser and Czar Nicholas II of Russia, stood him in good stead with the appropriate courts, though the growing friction among the European powers was perhaps beyond the control of anyone.

Moniker of the New King

While the prince’s diplomatic efforts were slowly grinding their way to limited success, Queen Victoria fell ill in December 1900 and her health deteriorated rapidly. She died on Jan. 22, 1901, and was succeeded by her son. To the surprise of virtually everyone, however, instead of adopting the title of Albert I, he chose to be called Edward VII, the first British monarch of this name for more than three centuries—since the death of the boy King Edward VI in 1553.

This went against the wishes of his mother, who had wanted him to be King Albert Edward. The new king explained the decision by saying that his father should be known forever as Albert the Good and his dutiful son would do nothing to change this. As far as Edward VII was concerned, there never would be a King Albert in Britain—and this does not seem likely in the near future, given that Charles and William are the next two princes in the line of succession.

Despite the continuing rift with Germany, which had been made worse by the Boer War in South Africa, the new king at first attempted a rapprochement with Kaiser Wilhelm, but had limited success. London then turned to France, and by 1904 the British and French had cemented their alliance, which was aimed principally at keeping Germany at bay.

In 1908, Edward VII visited Russia, where he and Nicholas II discussed further British arrangements with that country, a close ally of France. (It was made easier by the fact that Nicholas’ mother was the sister of Queen Alexandra, and therefore Edward was the czar’s uncle.) In due course, the British, French and Russian cooperation became known at the Triple Entente.

Preparations for New Portrait on Coins

The tradition in British coinage is that the portrait coins of a new ruler are not issued during the year that the old ruler died. For Edward in 1901, this meant that gold, silver and copper coins bearing Victoria’s visage continued to be struck and issued through the end of the year.

Behind the scenes, of course, there was increased activity as the London Mint prepared the necessary artwork and dies for the coinage of Edward VII.

In 1901, the chief engraver at London was George William de Saulles, a man with a superb talent for capturing the essence of a king or queen for the coinage. His rendition of Edward VII was well thought of by the public in 1902 and has stood the test of time.

De Saulles was, in addition, responsible for preparing the official coronation medals which carried the portrait of Queen Alexandra. The coronation was held on June 26, 1902, in line with the British tradition that it be carried out the following year after the monarch’s accession to the throne.

Unique 1902 Proof Set Enjoys Appeal

It also was traditional, in honor of the coronation, to issue a special proof set for collectors and government officials. The 1902 set, which used the newly fashionable matte finish, remains popular with modern collectors and brings strong sums at public auctions in the United States and Britain.

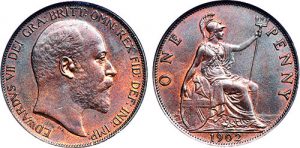

In some ways, the bronze coinage was the most easily dealt with by mint officials. The reverse designs in use under Victoria—all of Britannia—were simply kept and the portrait of Edward VII was placed on the obverse along with the appropriate titles in Latin. Translated, they read “EDWARD VII BY THE GRACE OF GOD KING OF GREAT BRITAIN DEFENDER OF THE FAITH [AND] EMPEROR OF INDIA.”

There were three bronze values—the penny, halfpenny and farthing (quarter penny)—and these were struck every year from 1902 through 1910. There are no rare dates among this coinage, although there are some mildly scarce pieces.

The farthing is rather special, as it was issued in a blackened finish. Some collectors have surmised that this was undertaken to deter hoarding, but actually it was done to avoid confusion with the gold half pound, which is about the same size.

The gold coinage was almost as easily handled as the bronze. For the 1902 proof set, there were four gold values—five pounds, two pounds, one pound and a half pound. All carried the famous depiction of St. George slaying the dragon on the reverse. This design had been prepared for the gold coinage in 1817 by famed artist-engraver Benedetto Pistrucci.

Account of Coins Minted Under Edward VII

The five- and two-pound pieces were struck for Edward VII only in 1902, but not just in proof. There also was a limited coinage of these two values in business-strike quality, but neither coin ever really circulated in the marketplace. On the other hand, the gold pound (usually called the “sovereign”) and half pound were struck every year under Edward VII and, as with the bronze, there are no rare dates.

The silver coinage is considerably more complicated than coins in the other two metals. One denomination, the silver crown (five shillings), was struck only in 1902, principally for the proof set but with a certain number in uncirculated finish.

The crown is an impressive coin and popular with those who collect the coins of Edward VII or just world crowns in general. The motif of St. George and the dragon was used for the reverse of the crown, but on none of the other silver pieces.

The half crown (two shillings, sixpence) retained the old reverse design from that of Victoria—a shield displaying various heraldic elements, but with a revised shield.

Exploring Florin Coins

Next in line was the florin (two shillings). The old reverse from 1901 was scrapped entirely here because the public had complained that the florin and half crown were too close in size and appearance.

For the florin, de Saulles prepared a superb rendition of a standing Britannia. It is said that the de Saulles version was the inspiration for the depiction of Britannia that has appeared on several modern British gold bullion coins. The artwork was especially admired at the time and continues to interest numismatists who appreciate better coinage designs.

The Victorian shillings had the monotonous shield reverse with heraldic elements, but de Saulles produced an exceptionally fine design showing a standing lion atop an imperial crown. As with the florin, this was much admired by the public and by later numismatists. The 1905 shilling has the distinction of being the rarest silver coin of Edward’s reign.

Sixpence and threepence silver coins were rather pedestrian in appearance and followed the Victorian designs, bearing merely a statement of value on the reverse—although the threepence did not have the word “pence,” only the numeral “3.”

The London Mint also struck small silver coins each year for the annual Royal Maundy ceremony, though these are not strongly collected today. A set consists of four pieces, from pence to fourpence. The Maundy coins usually were presented in little bags to the selected recipients, but also were available to numismatists on special order through the banking system.

The short reign of Edward VII not only produced some very good coinage designs, but also brought the monarchy back into public view.

Victoria had been a recluse for decades, but Edward reversed that policy to considerable public acclaim, and deserves to be better known today for his achievements.