Editor’s note: This is the second in a two-part series reflecting on coin auctions prior to Internet bidding being commonplace. Enjoy Part I >>>

By Greg Reynolds

While there are still physical bidders at major coin auctions, the percentage of rarities that go to Internet or “online” bidders have been trending upward since the early 2000s. Internet participation varies by auction firm and varies with each auction, but the upward trend is unmistakable. More and more rarities go to Internet bidders.

This trend has changed the nature of the bidding and the prices realized. While the positive and negative aspects of the role of Internet bidding in coin auctions are debatable, and subject to personal opinions, it is a fact that the atmosphere and the bidding activity in the pre-Internet area were much different from the atmosphere and bidding activity since 2015.

Has Internet bidding for rarities lead to higher prices realized than would have been realized if the Internet or something similar was never invented? There is not a clear answer.

Before the Internet, people who were unable or unwilling to attend auctions generally hired a coin expert to represent them, or they were telephone bidders. For expensive coins, hiring a coin expert to provide opinions regarding the lots still is a good idea regardless of the Internet.

During the 1990s and in the present, many coins in auctions are purchased by dealers for inventory, for customers, or for other purposes. One of the other purposes is to “crack out” coins from their PCGS or NGC holders and then resubmit them with the objective of receiving higher grades.

What percentage of the total dollar value of rarities auctioned during the last 15 years was purchased by bidders who were participating because of the ease of the Internet? Would these same buyers have been participating in auctions since 2005 if the Internet was never invented?

Many coin dealers and collectors of rarities would participate in auctions in the future if the Internet was never invented. Undoubtedly, some new bidders since 2005 will only participate if they are able to bid over the Internet, but how many have such an attitude, and how much have they bought?

A computing of the total dollar value of auction lots that were purchased by Internet bidders would certainly NOT show how much of a factor the Internet turned out to be in coin auction sales. Many of those same bidders would have participated if the Internet had never been invented.

When Dr. Duckor’s epic set of Saint-Gaudens double eagles was auctioned by Heritage in January 2012, the vast majority of the coins went to collectors, perhaps most of whom were bidding via the Internet. Nonetheless, each collector who likes to participate in auctions and is building a set of gem-quality Saints would probably find a way to participate in any auction of an epic set of Saints even if the Internet had never been invented. Hiring a coin expert or working through the respective auction firm would not have been the only two ways of participating without attending and without using the Internet.

Presumably, most Internet bidders decide their bids in advance of the auction. If the Internet did not exist or becomes crippled by hackers, a bidder who does not want to participate in person could just send a friend or relative to the auction, a trusted person who may know nothing whatsoever about coins. Someone who lives near the site of a particular auction could also be hired to execute bids for a collector. I am not saying that anyone should bid in a particular way; I am pointing out that it is unclear as to how many bidders participate due to the invention of the Internet. Even if the Internet had never been invented, most of the current Internet bidders for relatively expensive coins would just have found another way to bid. The use of cell phones is relevant.

While it is unclear as to how many new bidders for rarities the option of Internet bidding has attracted, it is clear that bidding activity was different during the pre-Internet era. Indeed, the whole culture of coin auctions was different. Three major differences come to mind.

1) Many leading bidders decided how much they would bid while the auction was in progress rather than in advance.

When I was writing auction reviews in the 1990s and early 2000s, I often had conversations with bidders, many of whom I met at coin shows. I am certain that most leading bidders then changed strategies, changed their budgets, or changed their maximum bids while auctions were going on. Their planned bids were continually changing for various reasons. They sensed the mood in the room. They gauged prices realized early on to try to figure “how the auction was going to go!” They noted whether many coins were being purchased by collectors or by dealers for inventory.

Bidders tried to sense trends in each particular auction. In one auction, Walking Liberty half dollars may have been hot, yet in an auction a month later, Walkers may have been cold and Morgan dollars may have been hot. Some bidders like to get on bandwagons while others like to be contrarians. If two bidders at one auction were bidding up coins of a particular series or particular sorts of type coins, other bidders may decide to stay away from those and concentrate on different coins in the same auction.

Veteran bidder Richard Burdick notes that “there were educational conversations at auctions. You learned about what others were interested in. You learned that experts disagreed about individual coins. You heard facts and opinions. Your bids were affected by what you heard and learned in the auction room and in the hallway.”

2) Some major bidders would take into consideration who they were bidding against while deciding when to stop bidding or whether to bid at all.

Egos, spiteful behavior, and business strategies all played roles in bidding competition.

It was common during the 1990s for an experienced bidder to take the buying practices of some of the other bidders into consideration. It mattered whether a bid for a particular lot came from a collector, a dealer representing a collector, an expert grader, a beginner, a careless buyer, a dealer seeking coins in his specialty, or a bottom feeder.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, a leading dealer in colonials was the top bidder for a large percentage of colonial coins sold at auctions. He would outbid collectors and other dealers. He wanted collectors of colonials to hire him to bid for them or to buy coins from him at coin shows. Additionally, he wholesaled colonial coins to other dealers.

Richard Burdick remembers that “before Doug Winter was the leader in the area, there was an East Coast dealer who specialized in Branch Mint gold coins. He would bid up and try to intimidate others who bid on Branch Mint gold coins in auctions.”

Richard also remembers “a leading dealer from New England who would often bid you up when he saw you bidding against him, to try to bury you, to try to break your spirit, to make it financially difficult for you to participate in the auctions.”

I vividly remember the same guy. During the early 1990s, I bid on a few patterns that I wanted to personally own. This dealer from New England did not allow me to buy any patterns for reasonable prices. Whenever he saw me bid, he just kept his paddle up until I stopped bidding. He bought so many coins in each auction that losing money on a few was part of his game.

It is also true that the same dealer who refused to allow me to buy any patterns for reasonable prices at auction would take the time to answer all my questions. We talked on many occasions. I learned from him.

Among coin people in attendance, educational conversations occurred before, during, and after auctions. When a series of coins that was not of interest to a particular bidder was being sold, he would often walk into the hallway and discuss coins with the others in the hallway. There were many interesting conversations and arguments about coins. I learned much about rarity, grading, and coin doctoring from those conversations.

Richard has very similar recollection. Indeed, he and I talked with each other and with others at many auctions in the 1990s.

“A lot of deals were cut in the hallway outside the auction room,” Richard notes. “There was a lot of debate and banter The auctioneers would come out and talk, too. It was fun to chat with other bidders. We talked about coins and argued about them. Everyone had opinions.”

At Stack’s (New York), lot viewing would often end at 4 p.m., and the auction would not start until after 6 p.m., so there was much time in between for fascinating conversations about coins. In the 1990s, human interactions were important aspects.

Andy Lustig has attended far more auctions than I have, and he began doing so earlier than I did. I remember seeing him at countless auctions from 1990 to 2021. He reveals that he began attending major auctions in the 1970s.

“For those of us who viewed the coins in advance, you could learn a lot about the coins at the auctions,” Andy remarks, “grading, value, rarity, etc. – by watching the bidders you respected.” Lustig adds that “you could learn from the pros by listening to their reactions to the prices paid, ranging from laughter at a really bad purchase to applause for a really great coin at a ‘macho’ price.”

Andy reminded me about the importance of noting bidding depth. “If two bidders were willing to spend more than $30,000 for a coin and no one else was willing to spend as much as $8,000, then it was sometimes the case that an auction price was a multiple of the wholesale value of the coin.” Also, if only not-so-knowledgeable bidders were interested in a coin, there might have been something wrong with the coin.

“Another advantage of live auctions,” Andy says, “is watching the number of bidders with hands in the air. When 20 hands were in the air, it was probably a risk-free price. If it’s only you and one other bidder,” Lustig says, “it’s probably a much riskier deal, even if you respect the other bidder. That real-time market feedback is completely lost in Internet auctions.”

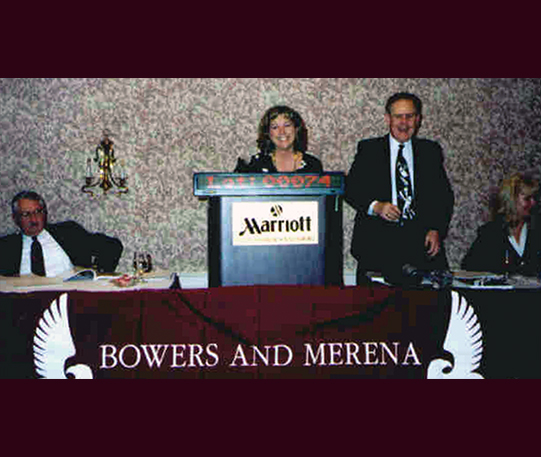

I recollect Andy as being one of the less emotional and more mild-mannered participants. Others would let their egos get in the way of their bidding or even scream hostile comments at their competitors. Some dealers wanted to prove they were grading geniuses by paying more than other expert graders for raw coins in Stack’s and Bowers & Merena auctions. They felt they could “get the grades” at PCGS or NGC that they needed to make money on the coins they bought at auction.

Andy became a coin expert while still a teenager. Even so, he reveals now that he “felt more comfortable” bidding against expert graders “who were buying coins for their own inventory.” I note that, during the 1990s, it was common for a not-so-knowledgeable bidder to be more likely to raise his paddle if he saw an expert grader bid on a coin that he was seeking.

Richard’s recollections are consistent with mine. “A collector-bidder or another dealer who might not be interested in a coin might become interested if he saw experts bidding on it. Some bidders would bid more if they saw that they were bidding against people who they think were experts,” he observed.

A few dealers had reputations for bidding sky-high prices for coins for their respective clients. I remember that most dealers were reluctant to get into bidding competitions with collectors or with dealers bidding for collectors. If a dealer buying for inventory found that he was competing with a collector, the dealer would often conclude that he was bidding too much and stop. While dealers seek to sell coins for profit, collectors are often buying for fun and were even more likely to become emotional.

During an auction around 1990 or 1991, I was talking to David, a leading collector, in the hallway outside the auction room at hotel in midtown Manhattan. Another collector, Herman, came by and started yelling obscenities at David. I stood there stunned while these two collectors rabidly called each other names. It soon became apparent that they were laughing and having fun, though one was somewhat angry at the other for outbidding him on some coins in a prior auction.

In the auction room, bidders often cracked jokes or made fun of their competitors. Richard and I remember that, if a bidder paid a seemingly very high price for a coin, it was common for someone to yell “you’re buried for life” at the buyer. Richard, Andy, and I all recollect that there was often cheering after a great coin sold for a strong price.

There was much talk in the auction rooms. It was common for an auctioneer to order bidders or onlookers to keep quiet, sort of like a judge orders people to keep quiet in a courtroom. The atmosphere was characterized by personalities and emotions.

Andy recollects that “auctions were then much more entertaining.” Richard asserts that, “if everyone was bidding on the Internet, much of the fun and competition would be lost.”

Bidding activity was sometimes surprisingly intense or surprisingly depressed. Egos clashed and tempers flared.

At auctions, some bidders became visibly happy while others sometimes became very upset. Most people at major coin auctions during the 1990s had a good time.

3) The energy or lack thereof in the room had an effect on the bidding.

Bidding “went crazy” during some auctions, and a sleepy atmosphere dampened bidding in other auctions. When bidding went crazy, prices were often well above the market levels in force at the time. More than a few dealer-bidders would pay much more for coins in such settings than they would for the same coins, hypothetically, on a bourse floor during the same time period.

After one very successful Stack’s (NY) auction in the early 1990s, Jim McGuigan, now a veteran dealer for more than forty years, walked up to me with a shocked and awed expression on his face. He declared to me that dealers in the auction room paid at least “30% more” for coins in the auction than they would have paid for the “same coins on the bourse floor” at a coin show.

Although auction moods are very difficult to explain, I am certain that some auctions became electrified. The excitement in the room caused some, though not all, bidders to pay much more than they would have paid if the auction had not become electrified.

Examples of auctions with electrified atmospheres are: the James A. Stack sale of January 1990, the sale of the L.A. Type set in October 1990, the Eliasberg sale of 1997, the sale of Eric Newman’s best U.S. silver coins in November 2013, and the Pogue II sale in September 2015. The Pittman II sale in May 1998 was in this same category, though not quite as lively.

Richard remembers the auction of Eliasberg’s gold coins by Bowers & Ruddy in October 1982. “You could hardly give a coin away on a bourse floor in September or October 1982. The market was terrible. It was overwhelmingly bad. We were near the bottom of a coin market, but all the energy in the auction room created higher prices. It was like a feeding frenzy.”

Internet bidding takes energy out of the auction room. When a group of people with common interests are in the same room, and snap decisions must be made, the behavior of the group often becomes unpredictable, and the group energy causes some individuals to behave in a way that they did not plan on behaving. A combination of factors leads to excitement in an auction room. Even though some bidders are agents for others, bidders must be physically present for this kind of excitement to come about.

How much of a factor is such excitement in the realm of coin auctions? No one knows for certain. The memories of exciting and entertaining coin auctions are very real to those of us who attended the events. For the effects of technological and cultural changes to be understood in the present, it is necessary to learn about the past.